The James Bond franchise’s newest addition, No Time To Die, was scheduled for release in April but was pushed to November due to the coronavirus pandemic.

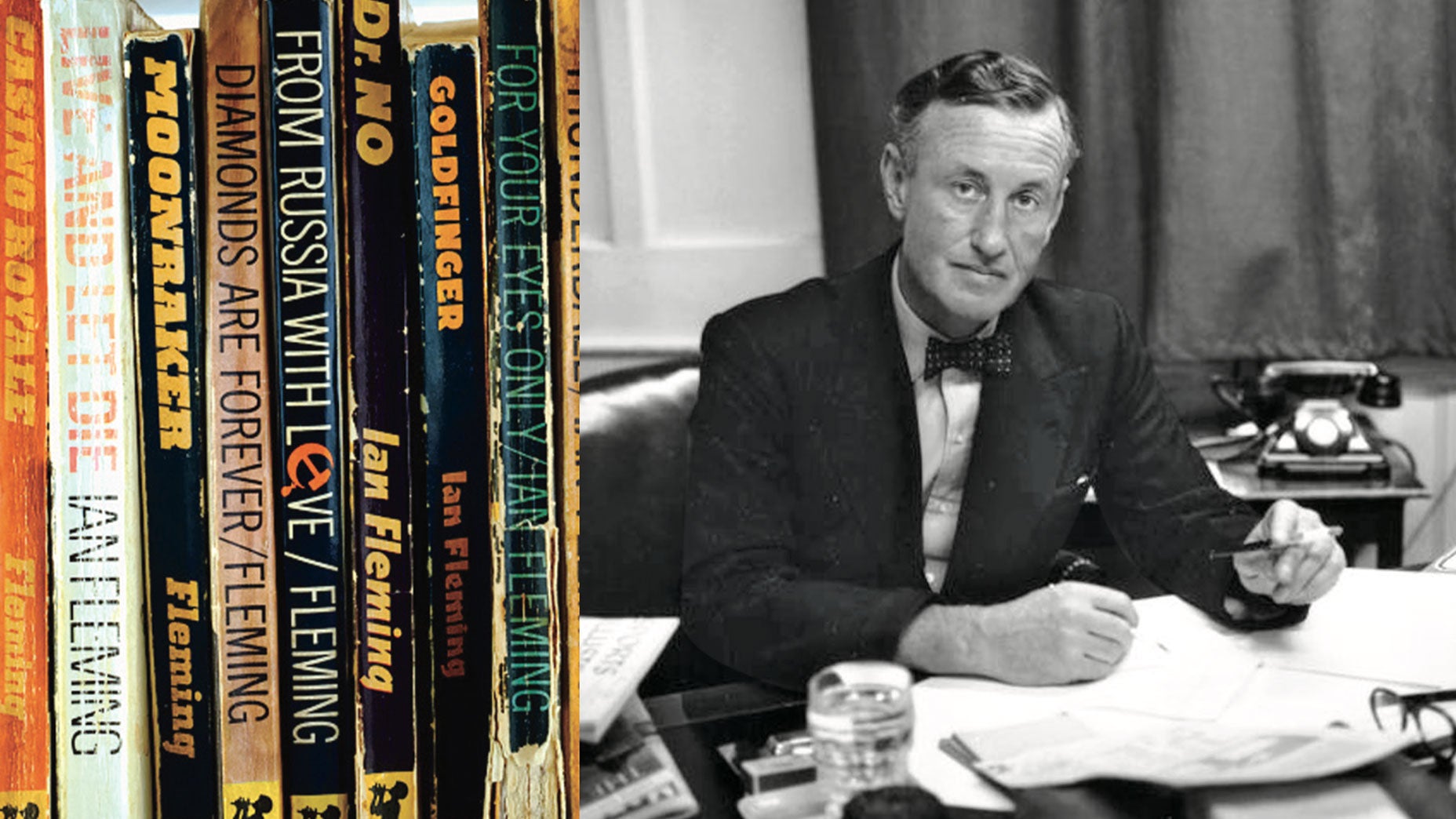

Fleming never came out and said that he was the model for James Bond, but he never exactly denied it either. The British author, who first introduced the dangerously debonair secret agent in his 1953 novel Casino Royale, had worked in naval intelligence during World War II. And while heâd mostly been stationed behind a desk, in his off-hours he played cards, drank and swapped stories with the real-life cloak-and-dagger spies who would provide the globe-trotting exploits of his best-selling 007 novels.

Like his fictional, licensed-to-kill creation, Fleming had a hedonistâs sweet tooth for fast cars and even faster women. But they also shared another passion â golf. Both Fleming and his alter ego had dog-eared copies of Tommy Armourâs How to Play Your Best Golf All the Time and Ben Hoganâs The Modern Fundamentals of Golf on his bookshelf. The two characters also shared a flat swing, a weak grip and a nine handicap â traits that are laid out in Flemingâs 1959 novel Goldfinger, which five years later would be turned into the third and best of all the Bond films thanks to its climactic golf match with the bullion-hoarding gold magnate (and flagrant golf cheat), Auric Goldfinger.

When it came to the sport, Fleming certainly knew what he was writing about. His first brush with the game came while attending prep school in Dorset. And shortly after his father â a well-to-do member of Parliament â died on the Western Front in World War I, he would spend his weekend afternoons with his grandmother at Huntercombe Golf Club, not far from Henley-on-Thames, where they would drive in her Rolls-Royce to play 18. She was a low handicapper with the decidedly eccentric habit of tipping her caddies with toothbrushes instead of cash.

In the years following World War II, Fleming would regularly play the courses at Gleneagles and Cooden in Sussex. But in 1948, while still in his pre-Bond bachelor years, when he was working as a journalist at the London Times, Fleming became a member at Royal St. Georgeâs, in Sandwich, Kent. After dictating the last of his newspaper columns for the week, heâd hop in his black Ford Thunderbird convertible with a set of American clubs in the backseat and drive to his weekend house in Sandwich, which was once owned by his close friend, playwright Noel Coward. But Flemingâs interest in golf was hardly for relaxation.

Although his swing off the tee wasnât easy on the eyes, what Fleming lacked in grace and form he made up for in enthusiasm. Like one of his most famous fans, John F. Kennedy â another golfer playboy who often had a 007 novel on his White House nightstand and who would name From Russia With Love one of his 10 favorite novels â Fleming enjoyed the clubby male companionship of the game, often wagering 50 pounds per match. Said Albert Whiting, then the head pro at St. Georgeâs, âHe was a great one to gamble on his games. He used to squeeze the last stroke out of his handicap. He made matches tough â the game would be deadly serious after the handicaps and bets had been fixed. He hated to lose. Everybody had to play like hell.â

Established in 1887, the 7,204-yard sweep of wild duneland at Royal St. Georgeâs was once named âthe greatest seaside golf course in the worldâ by the Financial Times. The private club has hosted the Open Championship 14 times â most recently in 2011. And itâs there that Fleming set one of the greatest fictional golf matches of all time.

In the 1964 film, Sean Conneryâs Bond (driving a gadget-festooned Aston Martin DB5 instead of a black Thunderbird) squares off with Gert Frobeâs nefarious Goldfinger at a golf club called âSt. Markâs.â Although filmed at Stoke Park, just a stoneâs throw from the 007 set at Pinewood Studios, the course in the movie is, for all intents and purposes, a thinly veiled version of Royal St. Georgeâs. The club pro in the film is named Albert Blacking (instead of Albert Whiting, the St. Georgeâs pro). And Bondâs caddie, his wily coconspirator against Goldfingerâs cheating, is named Hawker after the clubâs most sought-after bag carrier at the time, Alf Hawkes.

Fleming was a strict believer in golfâs gentlemanâs code and the rules of the game. Which is what makes Goldfingerâs under-handed tendency to improve an awful lie or substitute a lost ball with the assistance of his hulking, bowler-hatted man servant Oddjob all the more galling to Bond. It was an outward symbol of his immoral villainy. The wager may be a bar of Nazi gold valued at 5,000 pounds, but for 007 there is more at stake in his match with Goldfinger than just money. Itâs about honor â a battle between right and wrong, the values of the West triumphing over the corruption of SMERSH and the wickedness that lay on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Outwitting Goldfinger by switching his Slazenger 1 with a Slazenger 7 (Bond plays a Penfold Hearts) is the ultimate Cold War comeuppance.

In the film version of Goldfinger, the entire golf sequence is over and done with in a brisk nine minutes of screen time. But in Flemingâs novel, the match stretches out for 37 white- knuckle-tense pages, which also happens to be some of the best hole-by-hole golf writing ever to come pouring out of a typewriter â the âbrassie lies,â the âspoon,â the âblasterâ and âold hickory Calamity Janeâ in Bondâs bag.

And also some of the most colorfulâ¦

Goldfinger had made an attempt to look smart at golf and that is the only way of dressing that is incongruous on a links. Everything matched in a blaze of rust-coloured tweed from the buttoned âgolferâs capâ centred on the huge, flaming red hair to the brilliantly polished, almost orange shoes. The plus-four suit was too well cut and the plus-fours themselves had been pressed down the sides. The stockings were of a matching heather mixture and had green garter tabs. It was as if Goldfinger had gone to his tailor and said, âDress me for golf â you know, like they wear in Scotland.â

To readers who actually knew and had played Royal St. Georgeâs, the bookâs level of detail would have been strikingly familiar. The layout of each hole syncs up seamlessly with the layout of Flemingâs home course, something that would later become apparent to Connery when he finally played St. Georgeâs years after the film was released.

Although Connery certainly looked the part of a respectable golfer in the film â the jaunty, straw porkpie hat, the natty V-neck sweater and the smooth, fluid backswing â he was anything but at the time that Goldfinger was shot. Although heâd grown up in Scotland, the son of a factory worker was not a golfer. That would come later. Connery had been given lessons before the cameras rolled. âI never had a hankering to play golf,â he later said. âIt wasnât until I was taught enough golf to look as though I could outwit the accomplished Gert Frobe in Goldfinger that I got the bug.â

Flemingâs love affair with the game would continue until his premature death. Like the 007 of the novels, he smoked up to 80 custom-made Morland cigarettes a day. And a golf course is where he first felt the icy threat of an adversary more lethal than any of the iconic villains that 007 ever faced. During a golf getaway with his old Eton schoolmates at Rye, Fleming was taken ill with heart palpitations. Soon after, on August 11, 1964, he had his last lunch at his beloved Royal St. Georgeâs, where heâd by then become the clubâs captain-elect. In the early hours of the morning after, Fleming said goodbye â to Bond and to the game both of them adored.